| Insurance IP

Bulletin

An Information Bulletin on

Intellectual Property activities in the insurance

industry

A Publication of - Tom Bakos Consulting, Inc. and Markets, Patents and Alliances, LLC |

October 2008 VOL: 2008.5 |

||

| Adobe pdf version | Give us FEEDBACK | ADD ME to e-mail Distribution |

| Printer Friendly version | Ask a QUESTION | REMOVE ME from e-mail Distribution |

| Publisher Contacts

Tom Bakos Consulting, Inc.

Tom Bakos: (970) 626-3049 tbakos@BakosEnterprises.com Markets, Patents and Alliances, LLC Mark Nowotarski: (203) 975-7678 MNowotarski@MarketsandPatents.com Patent Q & A The Effect of In re: Bilski on Business Method

Patents Disclaimer:The answer below is a discussion of typical

practices and is not to be construed as legal advice of any kind. Readers

are encouraged to consult with qualified counsel to answer their personal

legal questions. Answer: It depends. Bilski will make it harder if you have a pure business method with no technology. But, if you specify a particular computer system required to implement your invention, Bilski may have no impact. Details: As we’ve reported earlier, the Bilski case raised the issue of whether or not a “pure business method” devoid of any particular technology was patentable. In 1997, Bernard Bilski and Rand Warsaw filed a patent application on a method they invented for hedging the risks associated with commodity markets. They wanted to get a patent on their fundamental method of hedging, without tying the claims to any particular computer implementation. It didn’t work. First they were rejected by the examiner. Then they were rejected by the USPTO Board of Appeals. And now, they’ve been rejected by the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC). It remains to be seen if they will appeal to the Supreme Court. This was not an easy case. The CAFC went to great lengths to review both its and the Supreme Court’s past decisions on what exactly you can and cannot get a patent on. They went all the way back to cases from the 19th century and ultimately came up with a new test to determine what sort of “process invention” is eligible for a patent. The new test is called the “machine-or-transformation” test. An inventive process is only eligible for patentable protection if it is either tied to a “particular machine” (e.g. a computer system) or transforms something into something else (e.g. lead into gold). For those inventing new

financial service products, the key question is “What is a ‘particular’

machine?” Unfortunately, the

Court did not address this issue.

That means we have to look to the USPTO to see what standards they

are setting for how particular a particular machine has to be. In the past, it was enough for a patent examiner if you simply said that at least a portion of your process was carried out on a computer. There was a recent Board of Appeals, case, however, that said no, you have to be more particular than that. It did not say how much more particular you had to be. The safest course, as far as we can tell, is to go “old school” in drafting your patent application. Before the 1998 State Street Bank decision, savvy patent agents went into great detail about exactly what sort of computer system was required to carry out a business method. They then tied the claims to that system. That still seems to work. For those business method inventors that are not particularly technically adept, it may be worthwhile to hire a tech consultant to spec out a particular system for you. You can then include that system in your patent application and list the tech consultant as a coinventor. The tech consultant then assigns his or her ownership rights back to you in exchange for their fee. Bilski is going to make life a little more challenging for business method inventors, but there are well tested strategies for coping. It’s important to put as much technology as possible in a patent application in order to pass muster with the new “machine-or-transformation” test.

Creating

Client Value with Peer-to-Patent Mark

Nowotarski (co-editor) will be conducting a

Workshop for

Optimizing Patent Strategies at Patent Forum 2009 on February 25 – 26, 2009 in San Francisco, CA.

The workshop will explore a powerful new tool for creating value for patent clients called Peer-to-Patent and how to use this new tool to potentially: · increase licensing / investor interest in a pending patent application, · identify and solve technical hurdles in an early stage invention, and · increase consumer interest in a new invention. The workshop will explore these goals through a fundamental redesign of patents which fully meet USPTO requirements made possible by the technology of Peer-to-Patent. Real life examples will be examined and participants will participate in patent drafting exercises based on peer-to-patent principles. Peer-to-Patent is a joint program between New York Law School and the USPTO to provide “open” patent examination. Applicants volunteer to have their patent applications posted on the Peer-to-Patent website. Members of the public may then upload prior art and commentary. The prior art and commentary is passed on to a USPTO examiner and the applications are examined right away.

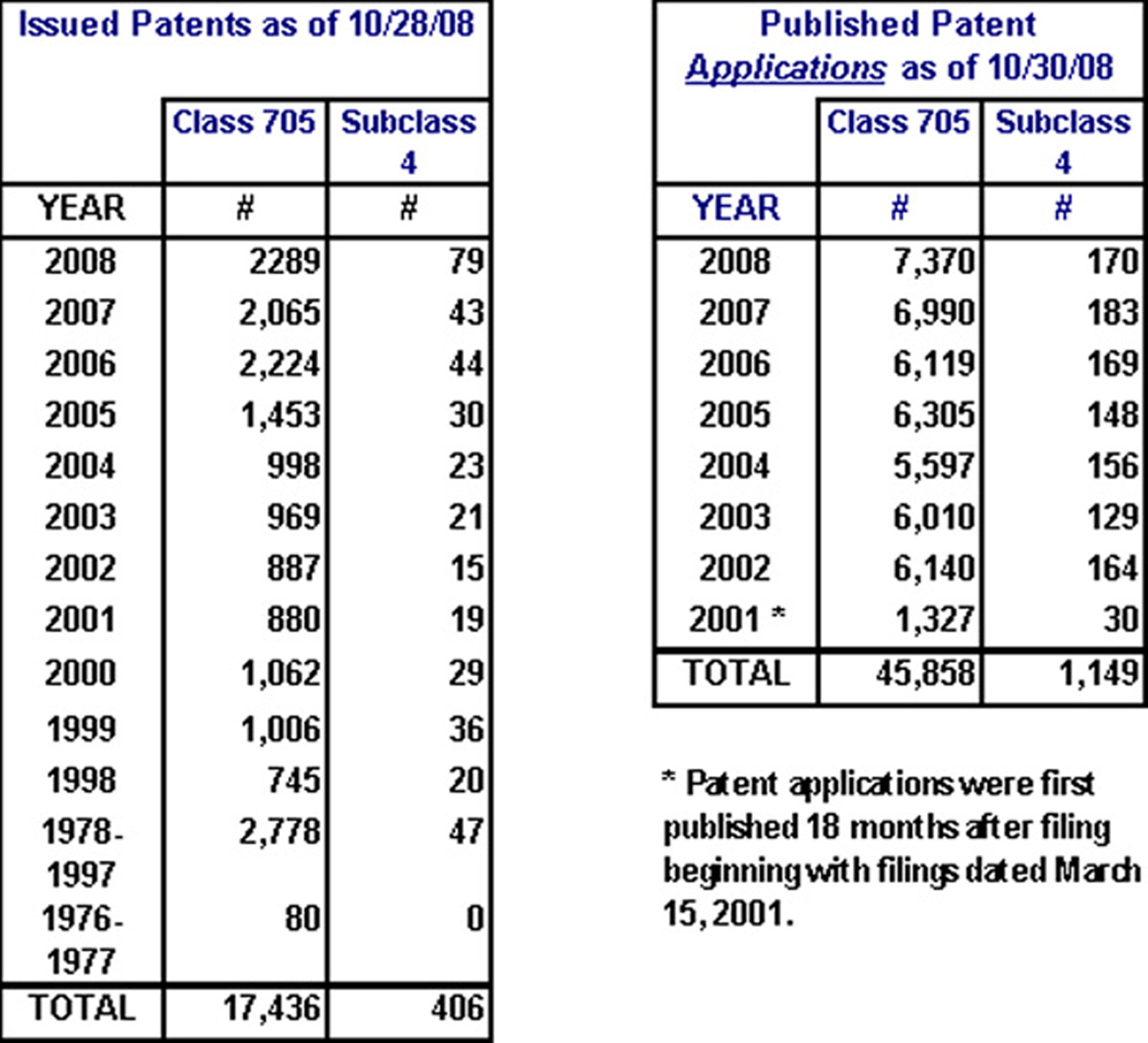

Lincoln National Life Insurance Company now has three patents covering the methods and processes used in providing Guaranteed Minimum Withdrawal Benefits (GMWBs) for variable annuities. Two additional patent applications remain pending. Lincoln is asserting its patent rights through patent infringement lawsuits against three competitors who offer GMWBs: Transamerica Life Insurance Company, Jackson National Life Insurance Company, and Sun Life Assurance Company. Claims in one patent are now the subject of a USPTO reexamination. GMWBs have been credited with saving the variable annuity industry and are commonly offered by many of the 25+ insurers currently selling variable annuity products. Lincoln National’s claim of protected patent ownership of the GMWB benefit is a threat to competitors offering GMWBs in the variable annuity market. Tom Bakos (co-editor of the Insurance IP Bulletin) has prepared a comprehensive Intellectual Property Analysis of the Lincoln National GMWB family of IP. This analysis (over 200 pages of printed detail plus supporting documents on CD) represents well over 200 hours of review, analysis, and dissection of the specifications and claimed inventions. It describes prior art (believed to be relevant) either not disclosed or not considered by the USPTO on examination. It addresses the quality of the claims made. For more information regarding this Analysis and how to acquire it, please go to: Intellectual Property Analysis (http://www.BakosEnterprises.com/IPA). Statistics An Update on Current Patent Activity The table

below provides the latest statistics in overall class 705 and subclass 4.

The data shows issued patents and published patent applications for this

class and subclass.

Class 705 is defined as: DATA PROCESSING: FINANCIAL, BUSINESS PRACTICE, MANAGEMENT, OR COST/PRICE DETERMINATION. Subclass 4 is used to identify claims in class 705 which are related to: Insurance (e.g., computer implemented system or method for writing insurance policy, processing insurance claim, etc.). Issued

Patents 15 new patents have been issued between 8/12 and 10/30/2008 for a total of 79 in class 705/4 during the first 10 months of 2008 – almost 8 new patents issued each month. Patents are categorized based on their claims. Some of these newly issued patents, therefore, may have only a slight link to insurance based on only one or a small number of the claims therein. The Resources section provides a link to a detailed list of these newly issued patents.Published Patent

Applications 43 new patent applications have been published between 8/14 and 10/30/08 for a total of 170 during the first 10 months of 2008 in class 705/4 continuing the pace of the prior two months and indicating a stable level of patent activity in the insurance industry in 2008 (about 17 new patent applications per month). The Resources section provides a link to a detailed list of these newly published patent applications.Again, a reminder - Patent applications have been published 18

months after their filing date only since March 15, 2001. Therefore, there are many pending

applications that are not yet published. A conservative estimate would be that

there are, currently, close to 250 new patent applications filed every

18 months in class 705/4. The published patent applications included in the table above are not reduced when applications are issued as patents, rejected, or abandoned. Therefore, the table only gives an indication of the number of patent applications currently pending. Resources Recently published issued U.S. Patents and U.S. Patent Applications with claims in class 705/4. The following are links to web sites which contain information helpful to understanding intellectual property. United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) : Homepage - http://www.uspto.gov/ United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) : Patent Application Information Retrieval - http://portal.uspto.gov/external/portal/pair Free Patents Online - http://www.freepatentsonline.com/

Patent Law and Regulation - http://www.uspto.gov/web/patents/legis.htm Here is how to call the USPTO Inventors Assistance Center:

Mark Nowotarski - Patent Agent services – http://www.marketsandpatents.com/ Tom Bakos, FSA, MAAA - Actuarial services – http://www.BakosEnterprises.com |

Introduction

In this issue’s feature article, Lincoln Reexam: Where Are the Experts?, co-editors Tom Bakos and Mark Nowotarski discuss how the set of Lincoln National Life patents covering GMWBs are about to get scrutiny not only in the courts but by the USPTO in a process called reexamination. We suggest that subject matter experts should have a role to play in these challenges and might have been helpful in protecting the patents from challenge in the first place if they had been engaged in the original examination of the patents. In our Patent Q/A, we discuss the effect that the recently handed down decision on Bilski may have on business method patents in the insurance and financial services industries. In addition, Jeremy Morton, a friend to the Bulletin, provides a European Union perspective on the Bilski decision.

The Statistics section updates the current status of

issued Our

mission is to provide our readers with useful information on how

intellectual property in the insurance industry can be and is being

protected – primarily through the use of patents. We will

provide a forum in which insurance IP leaders can share the challenges

they have faced and the solutions they have developed for incorporating

patents into their corporate culture.

Thanks, Tom

Bakos & Mark Nowotarski FEATURE ARTICLE Lincoln

Reexam: Where are the Experts? Co-Editors, Insurance IP Bulletin A hot set of insurance patents is getting tested in the courts and at least one is being further tested in a USPTO do-over called a “reexam”. These are the Lincoln National Life patents (6,611,815; 7,089,201, & 7,376,608) claiming various processes associated with the very popular Guaranteed Minimum Withdrawal Benefit (GMWB) commonly used with variable annuity products. This is a trillion dollar industry (that’s 12 zeros), so you can believe that the best counsel money can buy is being brought into play. What we’d like to know, however, particularly with respect to the reexam, is “Where are the Experts?” Lincoln has asserted its patent rights through filing patent infringement lawsuits against, so far, three insurance companies (Transamerica, Jefferson National, and Sun Life). This guarantees that these patents will be tested in the courts. In addition, an ex parte reexamination request was made and granted by the USPTO with respect to a limited number of claims in patent 7,089,201. The reexamination request was granted due to the submission of prior art that hadn’t been considered before and which raised a “substantial new question of validity”. Inventors seek patents to protect their inventions from unauthorized use or outright theft in order to preserve the significant value or effort the inventor invested in originating and developing his or her ideas. Getting a patent to issue is a significant step but it is certainly not the end of the process. Patents don’t enforce themselves. It is the patent owner’s responsibility to enforce the patent. If reminding potential infringers that you have a patent doesn’t work, then you must sue them in court. A cornerstone of any defense against infringement is to challenge the patent’s validity, but the law says that issued patents are presumed valid. The burden of proof to demonstrate invalidity in a court, therefore, is fairly high. Not so in a reexamination carried out at the USPTO. A characteristic of the reexamination process is that the patent office does not start with the presumption that the patent it issued is valid – at least with respect to the prior art issues that must exist in order to justify a reexamination request. There are two types of reexamination requests: · ex parte wherein the requester cannot participate in the reexamination beyond the initial request and filing a response to the patent owners statement, if made. · Inter partes wherein the requester may participate more actively by filing written responses to issues raised by the patent owner in response to the Office action letters produced by the patent office. The prior art cited by the requester must raise “a substantial new question of patentability”. The “existence of a substantial new question of patentability is not precluded by the fact that” the prior art was previously cited by, to, or considered by the patent office (35 U.S.C. §303). Expert affidavits might be submitted by the requester in order to help the patent office to determine whether or not a substantial new question of patentability exists. The Lincoln reexam is ex parte. No expert affidavits were submitted. If the anonymous requestor was serious about overturning the patent, then they have to give it their best shot when they file the request. After that, they are no longer part of the process. Which brings us back to the original question, “Why are there no expert opinions in the Lincoln reexam request?” There are knowledgeable and thorough explanations by patent attorneys, but it has been our experience that USPTO patent examiners give a lot more credence in sworn statements by experts. This is particularly true in insurance inventions where the in-house expertise in the patent office is limited. One possibility is that Lincoln itself requesting a reexam. This is not uncommon when a patent owner discovers previously unknown prior art. They submit it to the patent office in a reexamination request to make sure that it is considered before they enforce their patent. We don’t think that is the case here judging from the thoroughness and tone from the reexamination request, but it is an interesting tactic. When we reviewed the Lincoln National Life patent filings we also wondered why more use was not made of experts during the initial examination or even in the initial drafting of the patent. There is a lot of confusing aspects of this patent that could have been clarified if it had been properly reviewed beforehand. That might have avoided a lot of problems we see coming down the road in both the court infringement lawsuits and the reexam. See the August issue of the Bulletin and in particular Tom Bakos’ letter to Commissioner Dudas for more on these problems caused by lack of expertise. The

Lincoln court cases and reexamination case are important to the insurance

industry as a whole. Greater

use of experts in the drafting and examination of these patents might well

have clarified many of the issues now causing the disputes between the

parties. It’s not clear why

this hasn’t happened yet.

In Europe, the patentability of software-based inventions is a very hot topic, with the UK and the European Patent Office (EPO), respectively, often taking a different approach, and an increase in the activity of patent 'trolls' seeking royalties in the fields of finance, telecoms and e-commerce. Very recently the Court of Appeal in Symbian said that the UK Intellectual Property Office's approach was too narrow and that, although the EPO's approach was sometimes too broad, it was possible to reconcile the two for the most part - and that the English courts should always strive to follow EPO reasoning in this area. The UK patent examiners had been too tough on applicants for software-based patents.

Meanwhile, on October 22, 2008 the President of the EPO took the unexpected step of referring the question of software invention patentability to the Enlarged Board of Appeal, whose task is to ensure uniformity of interpretation of the European Patent Convention. The reference states that "Diverging decisions of the boards of appeal have indeed created uncertainty . . . Currently there are concerns, also expressed by national courts and the public, that some decisions of the boards of appeal have given too restrictive an interpretation of the breadth of the exclusion [of patentability for software as such]". Such references to the Enlarged Board are rare and in this case even more unexpected because the previous EPO President already refused to make a reference to the Enlarged Board on this subject when invited to do so by the English Court of Appeal in the Macrossan judgment. It is not clear why the new President now feels that a reference is appropriate, since nothing has changed about the way the EPO examiners look at software patents in the interim. This might call into question the procedural standing of the reference. But if it does go ahead, the result could be a narrowing of the rather broad approach taken by some EPO examiners when faced with software-based inventions. It is possible that the EPO wishes to reduce the volume of applications, by tightening up the rules. But some argue that this is only likely to result in more appeals, not fewer applications.

At the heart of both the US and European issues is the difficulty in defining the boundaries of patentability. The reference to the EPO Enlarged Board states that "It is hoped that the referral of these questions . . . will lead to more clarity concerning the limits of patentability in this field". The US court has clung to the notion of the transformation of physical materials, whilst in Europe the focus is on finding sufficient 'technical' content. In Symbian, Lord Neuberger (descending from the House of Lords to join the Court of Appeal panel for this case) suggested that it would be "dangerous to suggest that there is a clear rule available to determine whether or not a program is excluded [from patentability]". There is still much to be played for in terms of how business method concepts, particularly in areas like insurance, translate to the world of patentable computer technology.

Nevertheless, in Europe the prospects will remain extremely slim without hard technical elements to the invention, and even in the U.S. patent protection for insurance processes now looks like less and less of a sound investment.

|