|

Insurance

IP Bulletin

An Information Bulletin on

Intellectual Property activities in the insurance

industry

A Publication of - Tom Bakos Consulting, Inc. and Markets, Patents and Alliances, LLC |

October 15, 2005 VOL: 2005.5 |

||

| Adobe pdf version | FEEDBACK | ADD ME to e-mail Distribution |

| Printer Friendly version | QUESTION | REMOVE ME from e-mail Distribution |

|

Publisher Contacts

Tom Bakos: (970) 626-3049 tbakos@BakosEnterprises.com Markets, Patents and Alliances, LLC Mark Nowotarski: (203) 975-7678 MNowotarski@MarketsandPatents.com In Re LundgrenPatent Board of Appeals Releases Important Precedential Decision

A

major barrier to the possibility of directly patenting new insurance

products in the The USPTO board of appeals

has recently published a decision, In Re

Lundgren, where they have clearly said that inventions (in the

The decision is “precedential” which means that patent examiners have to follow it. The examiner corps is now drafting new examination guidelines that will enforce the decision. The immediate effect of

this decision is that we no longer have to say that a given insurance

process is carried out by technological means, such as a computer, in

order for it to be patentable in the

The longer term effects of this decision, however, could be much more profound. It opens the door to patenting inventions that are in what is now considered to be non-technological arts. While much of what is being done in the insurance industry (and financial services industry) today involves technology in that it is carried out on a computer, the added ability to seek patent protection on the non-technological arts include most of what the insurance industry does, such as underwriting methodologies and actuarial science, can add increased breadth to the patent protection provided.

It remains to be seen just how much the door will be opened, but at the very least, this decision increases the likelihood of being able to get more and better patent coverage for innovations in insurance and the financial services industry, in general. Patent Q & A Who Gets the Patent?Question: If I make an invention as part of my job, who owns the patent, me or my employer? Disclaimer: Patents are property. Questions of property ownership

rights are legal questions.

The answer below, therefore, is a discussion of typical practices

and is not to be construed as legal advice of any kind. Readers are encouraged to consult

with qualified counsel to answer their personal legal

questions.

2 If the patent

reform act currently before Congress is passed, then Corporations will be

able to apply directly for US patents. Patent SearchA New (Free) Patent Search Tool http://www.freepatentsonline.com is a new patent search tool where you can search and download patents images for free. The search engine is fairly powerful, but the collection is limited compared to what’s available on paid sites (e.g. www.delphion.com).

This site may give paid sites a run for their money when their collection expands. For those on a budget, however, it’s a good place to start. We have added it to our links. Track

the Progress of Pending http://portal.uspto.gov/external/portal/pair

lets you look over the shoulder of the patent examiner as a pending

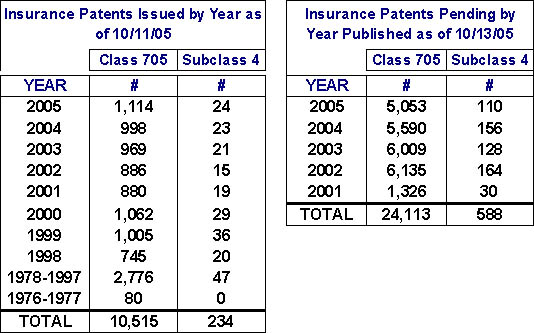

Statistics An Update on Current Patent Activity The table below provides the latest statistics in overall class 705 and subclass 4. The data shows issued and published patents and published patent applications for this class and subclass.

Class 705 is defined as: DATA PROCESSING: FINANCIAL, BUSINESS PRACTICE, MANAGEMENT, OR COST/PRICE DETERMINATION. Subclass 4 is used to identify claims in class 705 which are related to: Insurance (e.g., computer implemented system or method for writing insurance policy, processing insurance claim, etc.). Highlight of Newly

Issued Patents and Applications During Last Two Months

Issued

Patents Since our last issue 7 new patents with claims in

class 705/4 have been issued: 1 is L&H; 3 are P&C; and 3 can be

applied in all lines. All of

these new issues have Assignees recorded. Patents are assigned to classes

based on their claims. See the

detailed list for a brief description of these new patents.

Published Patent

Applications Thirty (30) new patent applications with claims in class 705/4 have been published since our last issue. They are broken down by product line or type area as follows: Health: 10 P&C: 7 Life: 6 All: 6 Pension: 1 TOTAL: 30

See the detailed list for of summary of

what has been recently published.

Again, a reminder

- Patent applications have been published 18 months after their filing date only since March 15, 2001. Therefore, there are many pending applications not yet published. A conservative assumption would be that there are about 150 applications filed every 18 months in class 705/4. Therefore, there are, probably, about 625 class 705/4 patent applications currently pending, only 473 of which have been published. Because the pending patents total above includes all patent applications published since March 15, 2001, applications that have been subsequently issued will also appear in the issued patents totals.

Resources Links to web sites with patent information. United States Patent and Trademark Office - HOME PAGE

Free Patents

Online

Patent Laws and

Regulation

Patent Agent Services

Actuarial Services |

In this issue we address the issue of “utility” as it relates to insurance and financial services type business method patents in our Feature Article “Will it Fly?”. This ties directly to our sidebar comment on the recent In Re Lundgren decision by the USPTO board of appeals. This decision removes the requirement that inventions must be in the “technological arts” (e.g. run on a computer) in order to be patentable. It may open the door, at least a crack, to the possibility of directly patenting new insurance products. We also point you to some free resources for doing patent research which are surprisingly useful. In the Statistics section we point out that Class 705/4 (insurance business methods) already has more patents issued through 10/11/05 (24) as in all of last year (23). And, it is apparent that patent activity in all of class 705 is ramping up. Enjoy the issue. Please let us know if you have any questions. Our mission is to provide our readers with useful information on how intellectual property in the insurance industry can be and is being protected – primarily through the use of patents. We will provide a forum in which insurance IP leaders can share the challenges they have faced and the solutions they have developed for incorporating patents into their corporate culture. Please use the FEEDBACK link above to provide us with your comments or suggestions. Use QUESTIONS for any inquiries. To be added to the Insurance IP Bulletin e-mail distribution list, click on ADD ME. To be removed from our distribution list, click on REMOVE ME. Thanks,

FEATURE ARTICLE Will it Fly? By: Tom Bakos & Mark Nowotarski

In the spring of 1903, two independent inventors,

Orville and Wilbur Wright, filed a patent application on a revolutionary

technology for controlling a flying machine. In that application they included

pictures of Orville flying it[1]. The reason they provided pictures was to show the

patent office that the invention actually worked. At that time the

We realize that the concept of “utility” is a difficult one to describe and understand because the common everyday meanings of the words used are often not applicable in exactly the same way in a patent examination. Patent examination is a process with its own field of art. It takes education and experience to apply it even to the level of “ordinary skill”. With that said, it is with trepidation that we embark on a discussion of “utility” in the field of insurance business method patents. But, we will do our best and hope to encourage comments, suggestions, and questions from our readers.

The utility requirement poses a challenge to those who would like to see patents granted directly on new insurance products instead of just on the technological inventions, such as novel computer systems, that enable them. Demonstrating that a new insurance product is useful and, therefore, works is a very different task than demonstrating that a technological invention works.

However, one final point on this before we go.

[1] Have a good eye for detail? Tell us what’s missing from this

“airplane” at

editors@insuranceIPbulletin.com.

|