| Insurance IP

Bulletin

An Information Bulletin on

Intellectual Property activities in the insurance

industry

A Publication of - Tom Bakos Consulting, Inc. and Markets, Patents and Alliances, LLC |

June, 2008 VOL: 2008.3 |

||

| Adobe pdf version | Give us FEEDBACK | ADD ME to e-mail Distribution |

| Printer Friendly version | Ask a QUESTION | REMOVE ME from e-mail Distribution |

| Publisher Contacts

Tom Bakos Consulting, Inc.

Tom Bakos: (970) 626-3049 tbakos@BakosEnterprises.com Markets, Patents and Alliances, LLC Mark Nowotarski: (203) 975-7678 MNowotarski@MarketsandPatents.com Now Available Lincoln National

Life Insurance Company Alleges Patent Infringement

- GMWB Lincoln

National Life insurance Company

was just issued a third patent (US 7,376,608) which now makes three

patents they own covering the methods and processes used in providing the

Guaranteed Minimum Withdrawal

Benefits (GMWBs). Two

additional patent applications remain pending. Lincoln

is asserting its patent rights through patent infringement lawsuits

against two competitors who offer GMWBs: Transamerica Life Insurance

Company and Jackson National Life Insurance

Company. Immediately

after their new patent was issued they sued Transamerica and Jackson

national for infringing it. GMWBs

have been credited with saving the variable annuity industry and are

commonly offered by many of the 25+ insurers currently selling variable

annuity products. Lincoln

National’s claim of protected patent ownership of the GMWB benefit, given

that they are enforcing their patent rights, is a threat to competitors

offering GMWBs in the variable annuity market. Tom

Bakos

(co-editor of the Insurance IP Bulletin) has

prepared a comprehensive Intellectual Property Analysis of

the Lincoln National GMWB family of IP. This analysis (over 200 pages of

printed detail plus supporting documents on CD) represents well over 200

hours of review, analysis, and dissection of the specifications and

claimed inventions. It

describes prior art (believed to be relevant) either not disclosed or not

considered by the USPTO on examination. It addresses the quality of the

claims made. This

analysis will be a valuable resource for anyone seeking a better

understanding to the Lincoln claimed inventions. For

more information regarding this Analysis and how to acquire it, please go

to:

Intellectual Property Analysis

(http://www.BakosEnterprises.com/IPA).

The Patent Office Allowed That?! Disclaimer:The answer below is a discussion of typical

practices and is not to be construed as legal advice of any kind. Readers are

encouraged to consult with qualified counsel to answer their personal legal

questions. Answer: No. Examiners are specifically required by law to disregard any input from third parties during an examination unless the applicant gives them written permission to do so. Details: It

used to be that pending US patent applications were kept secret until if

and when a patent issued. The

idea was to preserve the inventors’ secrets until they had their patents

in hand to prevent copying.

The Wright Brothers, for example, relied on this secrecy to prevent

the world from copying their plane until it was patented. The secrecy of pending patent

applications changed, however, when Congress passed the American

Inventor’s Protection Act

in the late 1990’s. This

required (with some exceptions) that patent applications be made public 18

months after a patent application’s earliest filing date. There was a fear, however,

particularly among independent inventors, that once patent applications

were published, deep pocket infringers would harass the patent examiners

with data and opinions to jam up the examination of a patent and keep it

from issuing. Hence 35

USC 122(c)

was added to the bill to require that the Patent Office make rules and

regulations so that “no protest or other form of pre-issuance opposition

to the grant of a patent on an application may be initiated after

publication of the application without the express written consent of the

applicant.” If

a third party sends in an inquiry to an examiner, it will not be replied

to. If a third party makes a

submission, it will not be acted upon. If a third party calls or leaves a

message for an examiner, it will not be accepted or

returned. That’s

not to say that there is nothing that a third party can do. The public has a

two month window

after an application is published to send in suggested prior art for the

examiner to consider, but they can’t add any commentary or explanations to

it and other restrictions apply.

This

is also not to say that an interested third party can’t publish their

opinions and suggested prior art on the Internet and hope that an examiner

looks at it. Some parties are

using Wikipedia for just such a purpose. The Peer-to-Patent

system

of public review of pending applications does give third parties the

opportunity to submit prior art and commentary before a patent application

is examined, but the inventors have to agree to allow their applications

to be commented on and no follow up is allowed once the examiner starts

working on the case. Given the unique challenges of examining financial service inventions, and in particular, the extraordinary breadth and depth of technical knowledge required for efficient and thorough examination, the time may be ripe to consider amending 35 USC 122(c), to allow for limited outside input into the examination of business method patents. Outside experts, for example, could help examiners understand what the applications mean. A properly regulated system of commentary by third parties could provide the technical assistance needed by examiners while actually helping inventors get higher quality patents in less time.

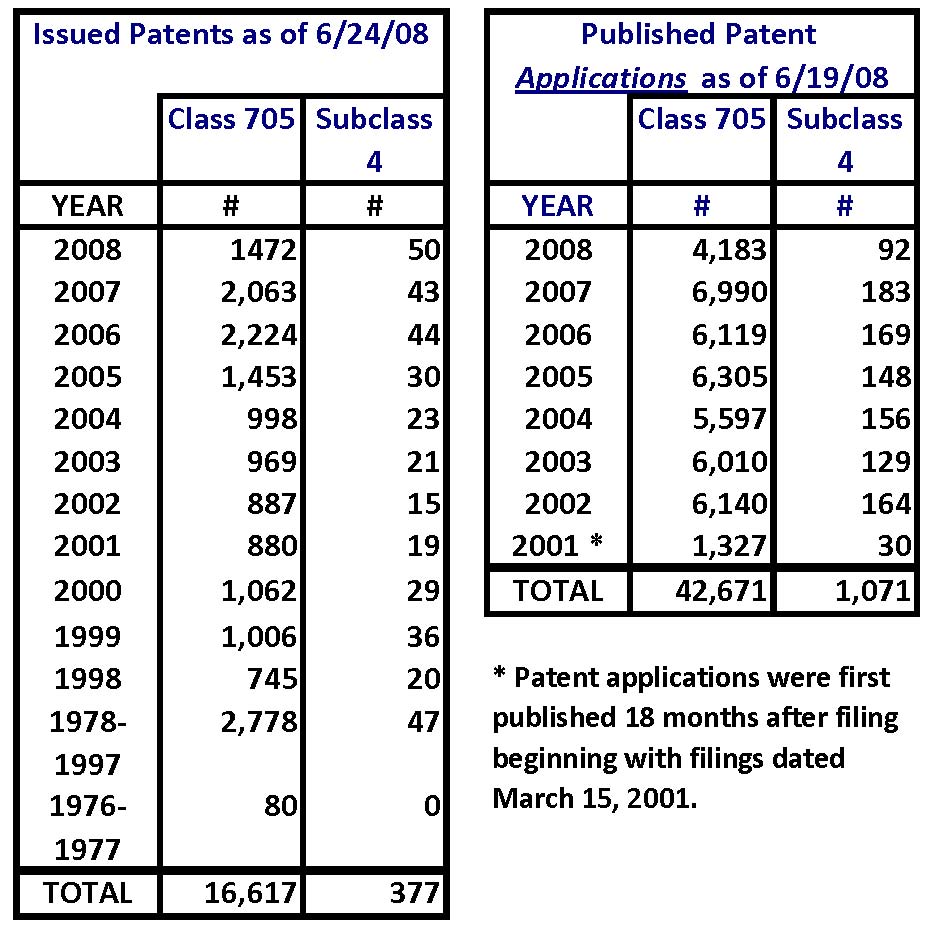

Statistics An Update on Current Patent Activity The table

below provides the latest statistics in overall class 705 and subclass 4.

The data shows issued patents and published patent applications for this

class and subclass.

Class 705 is defined as: DATA PROCESSING: FINANCIAL, BUSINESS PRACTICE, MANAGEMENT, OR COST/PRICE DETERMINATION. Subclass 4 is used to identify claims in class 705 which are related to: Insurance (e.g., computer implemented system or method for writing insurance policy, processing insurance claim, etc.). Issued

Patents 17

new patents have been issued during the last two months for a total of 50

in class 705/4 during the first 6 ½ months of 2008. Patents

are categorized based on their claims. Some of these newly issued

patents, therefore, may have only a slight link to insurance based on only

one or a small number of the claims therein. The Resources section provides a link to a detailed list of these newly issued patents. Published Patent

Applications 35

new patent applications have been published during the last two months for

a total of 92 during the first 6 ½ months of 2008 in class 705/4

continuing the pace of the prior two months and indicating a stable level

of patent activity in the insurance industry in 2008 (about 27

applications per month). The Resources section provides a link to a detailed list of these newly published patent applications. Again, a reminder - Patent applications have been published 18

months after their filing date only since March 15, 2001. Therefore, there are many pending

applications that are not yet published. A conservative estimate would be that

there are, currently, close to 250 new patent applications filed every

18 months in class 705/4. The published patent applications included in the table above are not reduced when applications are issued as patents, rejected, or abandoned. Therefore, the table only gives an indication of the number of patent applications currently pending. Resources Recently published issued U.S. Patents and U.S. Patent Applications with claims in class 705/4. The following are links to web sites which contain information helpful to understanding intellectual property. United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) : Homepage - http://www.uspto.gov/ United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) : Patent Application Information Retrieval - http://portal.uspto.gov/external/portal/pair Free Patents Online - http://www.freepatentsonline.com/

Patent Law and Regulation - http://www.uspto.gov/web/patents/legis.htm Here is how to call the USPTO Inventors Assistance Center:

Mark Nowotarski - Patent Agent services – http://www.marketsandpatents.com/ Tom Bakos, FSA, MAAA - Actuarial services – http://www.BakosEnterprises.com |

Introduction

In

this issue’s feature article, Best

Mode, co-editors Tom Bakos and Mark Nowotarski address a

patent requirement that may get overlooked if careful attention is not

paid to it during specification drafting. Any inventor who has considered

and come to a conclusion as to the best way to implement an invention is

required to disclose that best mode in the patent application. To not do so exposes any patent

issued to having claims invalidated. In

our Patent Q/A, we discuss how the USPTO

maintains strict confidentiality when examining a patent

application. Our

mission is to provide our readers with useful information on how

intellectual property in the insurance industry can be and is being

protected – primarily through the use of patents. We will provide a forum in which

insurance IP leaders can share the challenges they have faced and the

solutions they have developed for incorporating patents into their

corporate culture. Please

use the FEEDBACK link to provide us with your comments or

suggestions. Use QUESTIONS

for any inquiries. To be

added to the Insurance IP Bulletin e-mail distribution list, click on ADD

ME. To be removed from our

distribution list, click on REMOVE ME. Thanks, Tom

Bakos & Mark Nowotarski FEATURE ARTICLE Best Mode By: Tom Bakos, FSA, MAAA

& Mark Nowotarski According

to US patent law, in order to get a patent, the inventors are required to

make certain disclosures. The

inventors must not only describe how to make and use the invention (see

Enablement,

from our last issue), they must also “set forth the best mode contemplated

by the inventor of carrying out his invention” (35

U.S.C. 112,

first paragraph). This is

called the “Best Mode” requirement.

The word “contemplated” creates a two pronged inquiry into whether

or not the requirement has been met.

First there is a determination of whether a best mode was possessed

by the applicant. Then, if a

best mode existed, it must be determined whether or not the written

description disclosed it. Best

mode is subtle and subjective.

It is based on what was known by the applicant at the time the

application was filed. Events

or research following the filing of a patent application may reveal better

methods for carrying out the invention. An inventor, however, is not

required to update an application in order to disclose this subsequent

learning. The purpose of a

best mode disclosure requirement is to discourage an applicant from

holding back information they know at the time they file a patent

application is the best way to implement the invention. Without a best mode requirement

inventors would be able to get both patent protection and maintain a trade

secret. To

understand the nature of the Best Mode requirement and why it is

important, consider the recent non-insurance court case of TALtech

v. Esquel Apparel,

two Hong Kong based manufacturers of clothing. TALtech has a patent on how to

make a permanent-press shirt that doesn’t pucker when washed. The patent is US

patent 5,590,615,

“Pucker free garment seam and method of manufacture”. The inventor is John Wong, an

employee of TALtech. TALtech

sued Esquel Apparel for patent infringement in the US. During discovery, Esquel found

evidence that the inventor, Mr. Wong, had done numerous experiments with a

variety of different tapes to find just the right tape that would make the

process work. The result of

the experimentation was that Vilene SL33 was found to be the tape that

worked best and TALtech intended to use only Vilene SL33 in

production. TALtech’s patent

did describe a broad range of tape properties that would work, but it

didn’t disclose enough information for someone to know that Vilene SL33

would work much better than all other tapes evaluated. The court, therefore, ruled

that TALtech failed to disclose the best mode and the particular claims at

issue were ruled invalid. The

ruling was upheld on appeal. It’s

extremely unlikely that an examiner, reviewing only information provided

by the applicant, could determine if the best mode requirement had been

met. Hence patent examiners

are specifically told to “assume

the best mode requirement is met unless there is evidence to the

contrary”

and best mode issues are normally resolved during patent infringement

trials when an opposing party has an opportunity to find evidence related

to the intent of the inventor(s) at the time a patent was filed and facts

related to whether or not the best mode was disclosed. For example, the opposing party

would explore through document requests as part of the court proceeding

whether or not the inventors thought there was a better mode of enabling

the invention than what was actually disclosed in the specification. This judicial process would also

determine whether or not

enough disclosure was made in the specification to enable the best

mode. It

is quite possible that an inventor has not contemplated a best mode for

implementing an invention at the time a patent application is filed. That is, an inventor may know of a

number of ways to implement an invention and either all are equally

effective or each has advantages and disadvantages that make no single one

the best. In this case, the

inventor would have no best mode contemplated and, therefore, there is

effectively nothing to disclose.

However, practically the inventor may want to disclose all modes of

enablement (except for those known to be inferior) in order to avoid any

appearance of withholding important information from the disclosure.

The

disclosure has to be sufficient so that a person of ordinary skill in the

art can figure out how to practice the best mode without undue

experimentation. That is, the

disclosure can take into account (i.e. assume) what a person of ordinary

skill can be reasonably expected to already know. The inventors are not required to

identify which of a number of enablements they have described is the best

mode. They only have to make

sure that the method they believe to be the best mode is among the modes

described. The

fact that patent examiners are trained to assume that any enablements

described in a specification include a best mode implies that examiners do

not typically make rejections based on a failure to disclose best

mode. An applicant should not

use this examination quirk to take his or her focus off of the

requirement. Often inventions

are described in generic ways in order to receive the broadest possible

protection from a patent. In

the process, important detail necessary to implement a best mode may be

inadvertently omitted.

For

example, it’s very tempting to make broad sweeping disclosures (e.g. the invention disclosed herein uses advanced modeling

techniques…) that really don’t provide much practical detail in order

to get broader protection.

These disclosures run the risk of not being enabling of a best mode

if a specific modeling technique is known to produce the results required

for the invention to work as intended by the inventor. For example, the disclosure of a

specific modeling technique (e.g. the invention disclosed herein may be

implemented using XYZ modeling

software version X.0

…) may be required for the inventors to satisfy the best mode

requirement.

As noted, a high value patent will more likely than not get a court test. Failure to disclose a best mode is an argument typically made as a defense in an infringement lawsuit brought to enforce the inventor’s rights. Getting a patent issued is a difficult, time consuming process, and expensive process. In order to maximize the benefit of a patent a major objective should be to get a valid patent issued by being conscientious in avoiding applicant error and examiner mistakes. Forgetting about or purposely misleading by ignoring the best mode requirement can result in an invalid and unenforceable patent. |